Have you ever tried to time the second hand on your watch? The first thing you need is a more accurate time reference than the clock you are measuring. One of the hardest things to do is to measure how fast or slow a clock is running. Since then, the clock has been free from stoppages due to overweight pairs of pigeons. To counteract this, in February 2011, I fitted an anti-pigeon wire to the minute hand. The falling weight doesn’t have the power to lift two birds. And if two birds perch on the minute hand at quarter-to-the-hour, the clock will stop. This is no fault of the escapement, just a bad design flaw in the dial that means there is plenty of room for pigeons to sit on the hands. It didn’t last very long, however, and the college was soon without a clock. The clock tower was rebuilt to house the first clock in 1610 and in 1726 the then Master Bentley insisted on having one of his own. To this day, the best tower clocks in England use the gravity escapement – and the Trinity College clock is one of them. The well-established “remontoire” mechanism that was commonplace in Europe does a similar decoupling, but this new English gravity escapement is so much simpler and arguably more accurate.

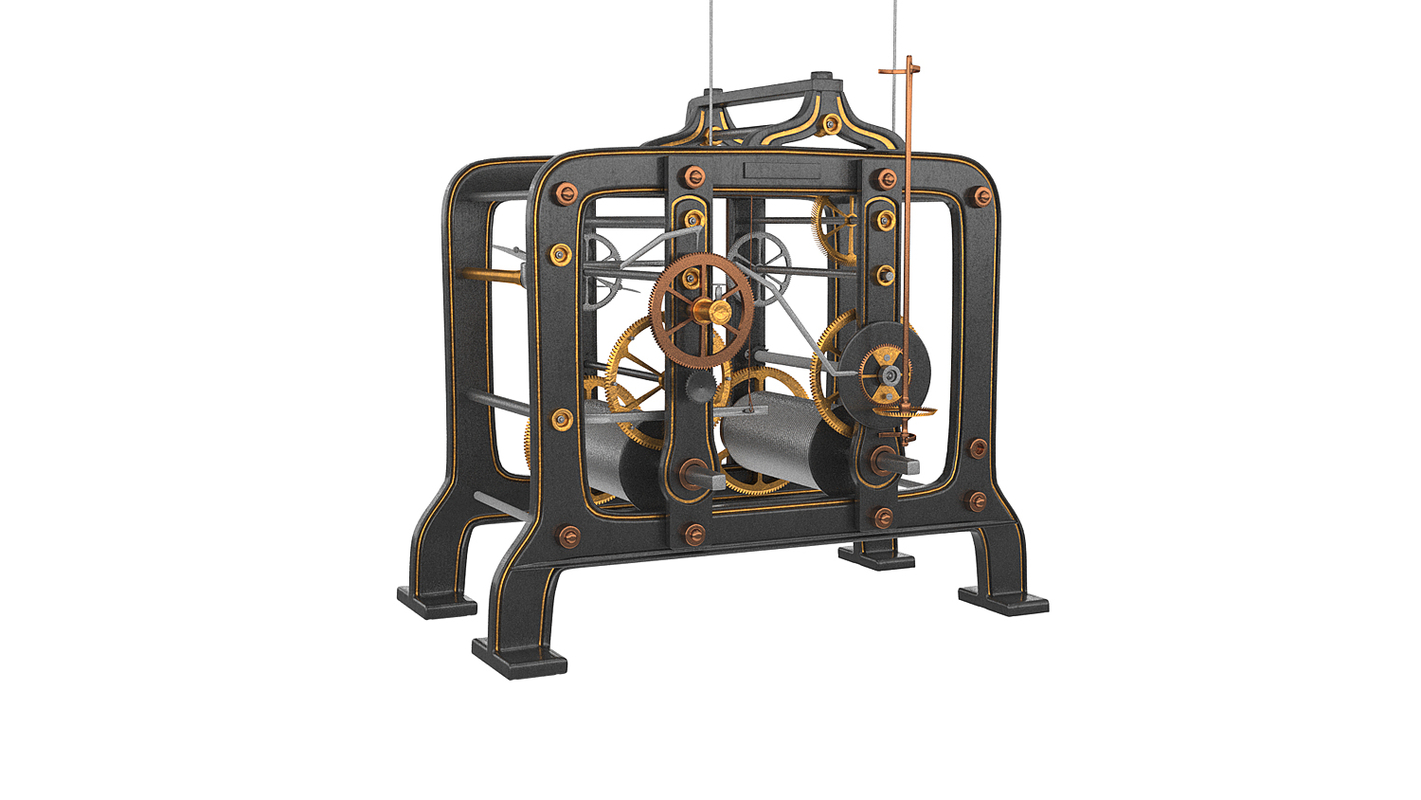

Denison’s “gravity” escapement has the virtue of remarkable accuracy because it decouples the driving force of the falling weights from the periodic force that maintains the motion of the pendulum. The weight also turns the hands of the clock. In a clock, the escapement converts the force of a falling weight into the periodic alternating impulses needed to keep the pendulum going. It was completed in 1859 and boasted Denison’s brand new “double three-legged gravity escapement”. It was designed by Edmund Beckett Denison, 1st Baron Grimthorpe, who was educated at Trinity College, and constructed by the famous clockmaker Edward John Dent.

The most famous tower clock is the one in London’s Elizabeth Tower, commonly known as “Big Ben” – although this actually is the name of its Great Bell. Its main function is to ring bells to announce the hour, and perhaps the half hour and quarters. The maker, Smith of Derby, had long been recognised for its top quality “tower clocks”, clocks that sit high up a tower, usually a church, and often have only one small dial. In 1910, a new clock was installed in Trinity College, Cambridge.

This is a brief history of time – or at least how one clock tells it.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)